How to Protect Yourself from Mysterious, Dangerous COVID-19

Graphic: V. Altounian/Science,

American Association for the Advancement of Science

September 14, 2020

We asked experts at GW Hospital to educate us about COVID-19 – from immediate concerns today to the future impact of the disease and ways to stop the spread of the virus. Here to discuss the path and impact of the virus on the human body is Sanjay B. Maggirwar, PhD, MBA, Professor and Chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Q&A with Sanjay B. Maggirwar, PhD, MBA

This Q&A was originally conducted in late March/early April, and updated in early July.

Q: What are your observations about COVID-19? How does it live in the body, what is its path of movement in the body, and what makes it different from other viruses?

Compared to the first severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus [which surfaced in 2002], SARS CoV2 is a very contagious microorganism. Its infectivity (ability to produce an infection) is much higher than expected, although we don’t yet know the exact numbers. Unlike seasonal flu, which generates symptoms within three days, the incubation time with this coronavirus is estimated in a range of up to 14 days, but averages between three to six days. The virus enters the body through the upper respiratory tract (ear, nose and throat), the ear being the most difficult entryway. Usually it enters through the nose, as the nasal cells' tiny hairs (cilias) work as a docking point for the virus, or the throat, where cells are also sensitive to infection, and travels downward to the lower respiratory tract, including the lungs. Like the flu, once the disease hits this area of the body, the symptoms become severe and much more difficult to treat.

Symptoms vary from person to person, but in general those inflicted with the virus experience fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, fatigue and a loss of sense of smell. While smell can be impacted by other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza, it is usually associated with nasal congestion, which is generally not the case with COVID-19. Researchers are working to better understand why and how the sense of smell is affected by the novel virus.

Some viruses can get into the blood and affect other tissues, such as the kidneys and brain. This is important because the brain controls the lung functions, especially breathing, and cognition. Based on early findings from China, we expect other tissues to be infected as well with COVID-19, including the liver, gastrointestinal track and heart.

Think you have COVID-19?

If you have symptoms of COVID-19 or have had close contact with someone who has had a confirmed positive COVID-19 test result, please seek medical attention by calling your provider's office. Virtual appointments are available with a GW healthcare provider.

Find out how to get tested ↗

Q: Why are some viruses more contagious than others?

SARS CoV2 (or the disease caused by them – COVID-19) is "novel," which means it has not been seen in humans until now. It's a brand new virus for the human population. Unfortunately, that also means our immune systems do not know how to defend us in the way they do against viruses we've been exposed to previously. It enters one's body and basically hijacks its cells, making the virus multiply. Very little of the virus is needed to start this process, so it is very easily spread from person to person.

Q: How long do viruses typically live outside the body, and how can they be spread?

Unlike droplets related to the typical cold or flu, which generally remain infectious for a few hours depending on where they land, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is suspected to live for hours to days on various surfaces including countertops and doorknobs. However, it is highly unlikely that the virus on the surfaces will remain infectious longer than an hour. This assertion is also echoed in the recent updates by the CDC. This is partly due to other factors that play a role in the longevity of a virus as well, such as seasonality, the amount deposited, and the chemistry of the virus, etc. The coronavirus, like most viruses, spreads through personal contact with someone who has the illness, but it can also occur by touching something – a doorknob or countertop – that has the virus on it and then touching entry points on your face, including the eyes, nose, mouth and ears. Recent reports suggest that the airborne virus (independent of those that are encapsulated in the droplets) may have a significant role in viral transmission; although this notion is quite alarming, it needs further validation.

Q: How can people best protect themselves from a virus?

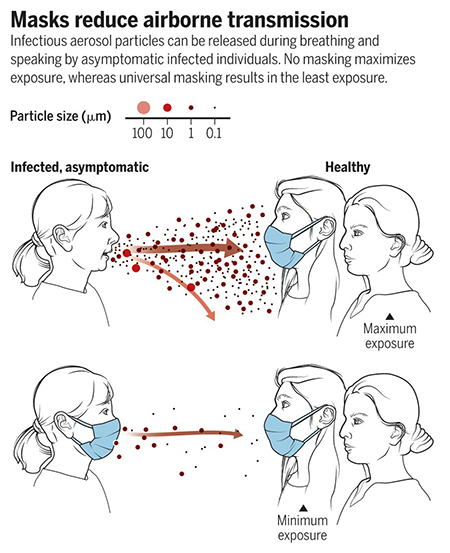

The best way to protect yourself from a virus is to avoid direct contact with those that have illness. Wash your hands often for at least 20 seconds, especially after touching things, and avoid touching your face. Keeping surfaces clean and maintaining social distancing are also effective ways to protect yourself. Masks over your nose and mouth prevent respiratory droplets from entering the air and your body. Wearing a mask may also protect others around you by reducing the transmission of respiratory droplets that you produce when you cough, sneeze, talk or raise your voice. Masks are encouraged to be worn every time you leave your home, but especially in areas of essential business. Have the mindset that everything is infected.

Q: What is the life cycle of COVID-19, and what is the body’s response?

As with most pathogens, SARS CoV2 takes 18-20 hours to multiply and infect millions of other cells. In three to six days, the body responds in two ways: the foreign pathogen enters circulation, which triggers the production and secretion of defensive proteins that alert other uninfected cells and make them ready to fight and neutralize or inhibit the pathogen. This reaction is why we feel feverish. Taking ADVIL® or ibuprofen will worsen the situation, so it is advised to avoid these medicines (of course, if the fever is very high, medical attention should be sought). Second, T-cells (defensive cells) start identifying and learning about the pathogens and then start producing more T-cells that are now specialized in killing them (or the infected cells). This can take 8-10 days. B-cells produce antibodies in a shorter amount of time and then the macrophages (cells designed to engulf other pathogens, imagine them being like Pac Men) eat virally infected cells.

Q: Why does COVID-19 impact certain people more or differently than others?

Viruses affect people differently than others for a variety of reasons. Some people have strong immune systems with more reactive T-cells, B-cells, etc. They may have been exposed to non-pathogenic versions of SARS in the past and already have antibodies in their system, which may make them somewhat resistant to the virus. Other factors include lifestyle, age and underlying conditions, such as hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetes, cancer/HIV, etc. Smokers are also more susceptible to the disease because smoking damages the lungs and weakens the immune system, reducing the body’s ability to fight viruses. It also contributes to problems like heart disease, which is a risk factor for COVID-19.

Sanjay B. Maggirwar, PhD, MBA, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. A microbiologist with extensive experience researching HIV, he is among a group of professionals at the George Washington University who are sharing ideas and skills that could be used in the studies aimed at understanding and quelling the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sanjay B. Maggirwar, PhD, MBA, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. A microbiologist with extensive experience researching HIV, he is among a group of professionals at the George Washington University who are sharing ideas and skills that could be used in the studies aimed at understanding and quelling the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read more from Dr. Maggirwar in the Washington City Paper article, "Do Bars and Restaurants Need to Scrap Silverware for Single-Use Plastic Utensils?"